In their third blog postings, the students examined the relationship between art and life in Jean Rhys's fiction and her memoir Smile Please. The following sample student blog posting by Davira Widianto addresses the significance of L'Arlesienne in Rhys's Good Morning, Midnight:

The opening of the second part of Good Morning, Midnight got me really excited because of one thing in particular: L’Arlesienne. The common layman might not know this piece, but it is one of the most famous classical pieces of all time because of its strong, demanding line that most everyone has heard of before (and just didn’t know the name of–look it up!). Upon doing more research of the piece, however, I found that the music has more to do with the tempo at which Sasha walks to as she meets the strange man who asks her over for dinner. “Walking to the music of L’Arlesienne,” (Rhys 86, 91), Sasha connects to the music at a theatrical play level as well as a musical level, and the story behind L’Arlesienne flows with the actual events going on in Sasha’s life at that moment.

L’Arlesienne was a play before it was made popular as a piece composed by Bizet three years later, and it tells the story of a man who falls in love with an unfaithful girl. Her infidelity drives this man mad, and despite his family’s pleas and attempts to convince him otherwise, he takes his own life due to this madness (L’ARLESIANA). Not much is known about the play other than the bare plot because it was so unsuccessful (because of the complexity of the plot), but Jean Rhys didn’t include this specific piece just because it was the first thing that came to her mind as she wrote it. There exists parallels between the play’s plot and Sasha’s life, exemplified in the very beginning of Part 2 alone; as she claims to walk to the beat of L’Arlesienne, you could argue that she’s living through the play’s story. Right after mentioning the play title, for example, Sasha ponders killing herself with chloroform, and we learn later on in Part 3 that it may have to do with the spiralling depression she’s been stuck in after Enno had so casually left her (which, again, coincided with Sasha’s attempt at infidelity with one of her English students). Coincidence? I think not.

The music itself alternates between self-righteous march, strong and powerful, in a minor key, to a more major, feminine, optimistic tone (with the same melodic line). It’s repetitive, but it isn’t. It’s the same thing…except it’s not. It seems to fit well with Sasha’s lifestyle; she lives through the repetitive eat-sleep-repeat motions, but her thoughts are always a wild scramble of suicide, food, music, and judgment of character. Another connection at a musical level.

Then there’s the word itself: L’Arlesienne. It never had the debut it needed to become popular, but the French now use it as a colloquial term to describe a person who is “prominently (and sometimes voluntarily) absent from a place or a situation where they would be expected to show up” (L’Arlesienne). Almost flaneur-like, in a way, except used for women who are in places with people they shouldn’t be. Sasha embodies this definition quite well, the flaneur and the arlesienne.

This overall pattern of misdirection (or even no direction at all) as seen in the pairing of Sasha and L’Arlesienne can also be expanded to see the parallels of the events in Good Morning, Midnight and Jean Rhys’s own life. She hadn’t lived the best of lives, though I’ll admit she has more to be thankful for than she lets on. Despite all this, Jean Rhys maybe has a little bit of her own L’Arlesienne inside of her, this sense of not belonging, or not being in place she should belong. She was always posed as different from the rest of her family through a racial and even physical lens: “[Rhys] hated the name Gwendolen (which she learned means white in Welsh), just as she hated being the palest of her siblings” (Savory 1). She feels like the outsider looking in, just like Sasha does as an American in Paris, and this attitude bleeds into the novel’s protagonist whether she intends to or not because that’s simply part of who she is. To say that authors have to disengage their writing from their personal life would take out the flavor of many works of fiction, so I’d personally let them self-indulge a bit as long as it was entertaining.

Elkins’s point on biographies, though, still stands true when it comes to an overdone self-portrayal: “[Biography] confuses fiction and reality so that instead of elucidating the artist’s life, it further confuses the matter” (Elkin). In her criticism of Pizzichini’s work, there are clear differences between the biographer’s words and Rhys’s own so that you can almost tell it isn’t written by someone who really knew Rhys. Even by comparing the voices in Good Morning, Midnight and The Blue Hour, there’s a missing element of irony and aloof self-deprecation that makes Rhys so interesting and jarring. Pizzichini didn’t take into account Rhys’s complete attitude towards life that would make her have so developed a tone, and it definitely shows. I couldn’t be able to read Pizzichini’s work and say “Ok, Rhys embodies L’Arlesienne, she embodies the flaneur.” The voice just doesn’t fit.

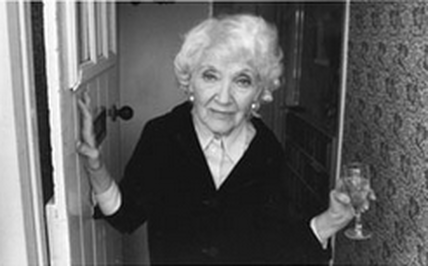

With this in mind, here’s a picture of the real late and great Jean Rhys: opening a door, glass of champagne in her hand, from the outside looking in. Even her pictures can symbolize her life’s work and life story. I chose the photo below of her because of her pose, as if she were acting the part of Sasha in her own novel. I almost imagine it as a screening for a movie, and she’s a dead ringer for the part because…well, Sasha is Jean Rhys, in a way. Many critics will argue back and forth about the ethics of it all, but it won’t change the way we, as readers, see this connection between author and character. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Works Cited

Elkin, Lauren. “When a Biography Is Not a Biography: The Blue Hour: A Life of Jean Rhys.” Quarterly Conversation RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Sept. 2014.

“L’ARLESIANA.” L’Arlesiana : Synopsis. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Sept. 2014

“L’Arlesienne.” Wikipedia Dictionary. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Sept. 2014.

Rhys, Jean. Good Morning, Midnight. New York: Shoreline, 1986. Print.

Savory, Elaine. “Life.” Introduction. The Cambridge Introduction to Jean Rhys. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2009. N. pag. Print.

The opening of the second part of Good Morning, Midnight got me really excited because of one thing in particular: L’Arlesienne. The common layman might not know this piece, but it is one of the most famous classical pieces of all time because of its strong, demanding line that most everyone has heard of before (and just didn’t know the name of–look it up!). Upon doing more research of the piece, however, I found that the music has more to do with the tempo at which Sasha walks to as she meets the strange man who asks her over for dinner. “Walking to the music of L’Arlesienne,” (Rhys 86, 91), Sasha connects to the music at a theatrical play level as well as a musical level, and the story behind L’Arlesienne flows with the actual events going on in Sasha’s life at that moment.

L’Arlesienne was a play before it was made popular as a piece composed by Bizet three years later, and it tells the story of a man who falls in love with an unfaithful girl. Her infidelity drives this man mad, and despite his family’s pleas and attempts to convince him otherwise, he takes his own life due to this madness (L’ARLESIANA). Not much is known about the play other than the bare plot because it was so unsuccessful (because of the complexity of the plot), but Jean Rhys didn’t include this specific piece just because it was the first thing that came to her mind as she wrote it. There exists parallels between the play’s plot and Sasha’s life, exemplified in the very beginning of Part 2 alone; as she claims to walk to the beat of L’Arlesienne, you could argue that she’s living through the play’s story. Right after mentioning the play title, for example, Sasha ponders killing herself with chloroform, and we learn later on in Part 3 that it may have to do with the spiralling depression she’s been stuck in after Enno had so casually left her (which, again, coincided with Sasha’s attempt at infidelity with one of her English students). Coincidence? I think not.

The music itself alternates between self-righteous march, strong and powerful, in a minor key, to a more major, feminine, optimistic tone (with the same melodic line). It’s repetitive, but it isn’t. It’s the same thing…except it’s not. It seems to fit well with Sasha’s lifestyle; she lives through the repetitive eat-sleep-repeat motions, but her thoughts are always a wild scramble of suicide, food, music, and judgment of character. Another connection at a musical level.

Then there’s the word itself: L’Arlesienne. It never had the debut it needed to become popular, but the French now use it as a colloquial term to describe a person who is “prominently (and sometimes voluntarily) absent from a place or a situation where they would be expected to show up” (L’Arlesienne). Almost flaneur-like, in a way, except used for women who are in places with people they shouldn’t be. Sasha embodies this definition quite well, the flaneur and the arlesienne.

This overall pattern of misdirection (or even no direction at all) as seen in the pairing of Sasha and L’Arlesienne can also be expanded to see the parallels of the events in Good Morning, Midnight and Jean Rhys’s own life. She hadn’t lived the best of lives, though I’ll admit she has more to be thankful for than she lets on. Despite all this, Jean Rhys maybe has a little bit of her own L’Arlesienne inside of her, this sense of not belonging, or not being in place she should belong. She was always posed as different from the rest of her family through a racial and even physical lens: “[Rhys] hated the name Gwendolen (which she learned means white in Welsh), just as she hated being the palest of her siblings” (Savory 1). She feels like the outsider looking in, just like Sasha does as an American in Paris, and this attitude bleeds into the novel’s protagonist whether she intends to or not because that’s simply part of who she is. To say that authors have to disengage their writing from their personal life would take out the flavor of many works of fiction, so I’d personally let them self-indulge a bit as long as it was entertaining.

Elkins’s point on biographies, though, still stands true when it comes to an overdone self-portrayal: “[Biography] confuses fiction and reality so that instead of elucidating the artist’s life, it further confuses the matter” (Elkin). In her criticism of Pizzichini’s work, there are clear differences between the biographer’s words and Rhys’s own so that you can almost tell it isn’t written by someone who really knew Rhys. Even by comparing the voices in Good Morning, Midnight and The Blue Hour, there’s a missing element of irony and aloof self-deprecation that makes Rhys so interesting and jarring. Pizzichini didn’t take into account Rhys’s complete attitude towards life that would make her have so developed a tone, and it definitely shows. I couldn’t be able to read Pizzichini’s work and say “Ok, Rhys embodies L’Arlesienne, she embodies the flaneur.” The voice just doesn’t fit.

With this in mind, here’s a picture of the real late and great Jean Rhys: opening a door, glass of champagne in her hand, from the outside looking in. Even her pictures can symbolize her life’s work and life story. I chose the photo below of her because of her pose, as if she were acting the part of Sasha in her own novel. I almost imagine it as a screening for a movie, and she’s a dead ringer for the part because…well, Sasha is Jean Rhys, in a way. Many critics will argue back and forth about the ethics of it all, but it won’t change the way we, as readers, see this connection between author and character. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Works Cited

Elkin, Lauren. “When a Biography Is Not a Biography: The Blue Hour: A Life of Jean Rhys.” Quarterly Conversation RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Sept. 2014.

“L’ARLESIANA.” L’Arlesiana : Synopsis. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Sept. 2014

“L’Arlesienne.” Wikipedia Dictionary. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Sept. 2014.

Rhys, Jean. Good Morning, Midnight. New York: Shoreline, 1986. Print.

Savory, Elaine. “Life.” Introduction. The Cambridge Introduction to Jean Rhys. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2009. N. pag. Print.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed